Our Work / Stewardship

Wolf Preserve Trails & Species

To provide the community with a place to breathe and connect with nature is what Mrs. Leonor D. Wolf hoped for when she donated the Wolf Preserve to the Peconic Land Trust in 2003.

Trails

The preserve’s 23 acres today provide that connection to the community. The two nature trails winding through the property were opened to the public in 2006.

In the Fall of 2020, the 1/3 mile Eastern Trail Loop was renovated and:

- widened to six feet to accommodate wheelchairs

- leveled to maintain an approximate grade of 0-3%

- expanded to include experiences of scenic vistas and unique habitats

- improved with woven textile fabric to extend the trail’s lifespan, and

- stabilized with a natural stone blend to harden the surface.

The design of the Eastern Trail Loop’s meandering path is more than just beautiful. It will help prevent washouts during storms. Wind your way through a mature woodland featuring oak and beech trees, with great wetland habitat for both migrating birds and waterfowl.

The 1/2 mile Western Trail Loop takes you through the meadow and into the dense red cedars of the regenerating woodland. While this part of the property had been farmed for many years, Mrs. Wolf allowed it to revert to its natural state to provide wildlife habitat. Wander along the the wetlands, and keep your eyes open for waterfowl, reptiles, and amphibians.

The eco-friendly updates used in the Eastern Trail Loop were used again when the Western Trail Loop and the Meadow Loop were renovated in the Fall of 2021. Future trail enhancements include a boardwalk across the wetlands, a bridge to connect the Eastern and Western Trail Loops, and an expanded parking lot.

The Trust’s Harold A. Reese Preserve, acquired in 2020, borders the Wolf Preserve to the southeast and expands the conserved area on the Great Hog Neck peninsula by 30 acres. A trail runs from Main Bayview Road to North Bayview, linking the two preserves, showcasing several important ecosystems and the native species who live there.

Animals

American Bullfrog

Lithobates Catesbeianus

Bullfrogs get their name from the sound that males make during the breeding season, which resembles a bull bellowing. The males make at least two different sounds: a mating sound and a warning call. A bullfrog can jump up to 10 times their body length- almost as far as 6 feet!

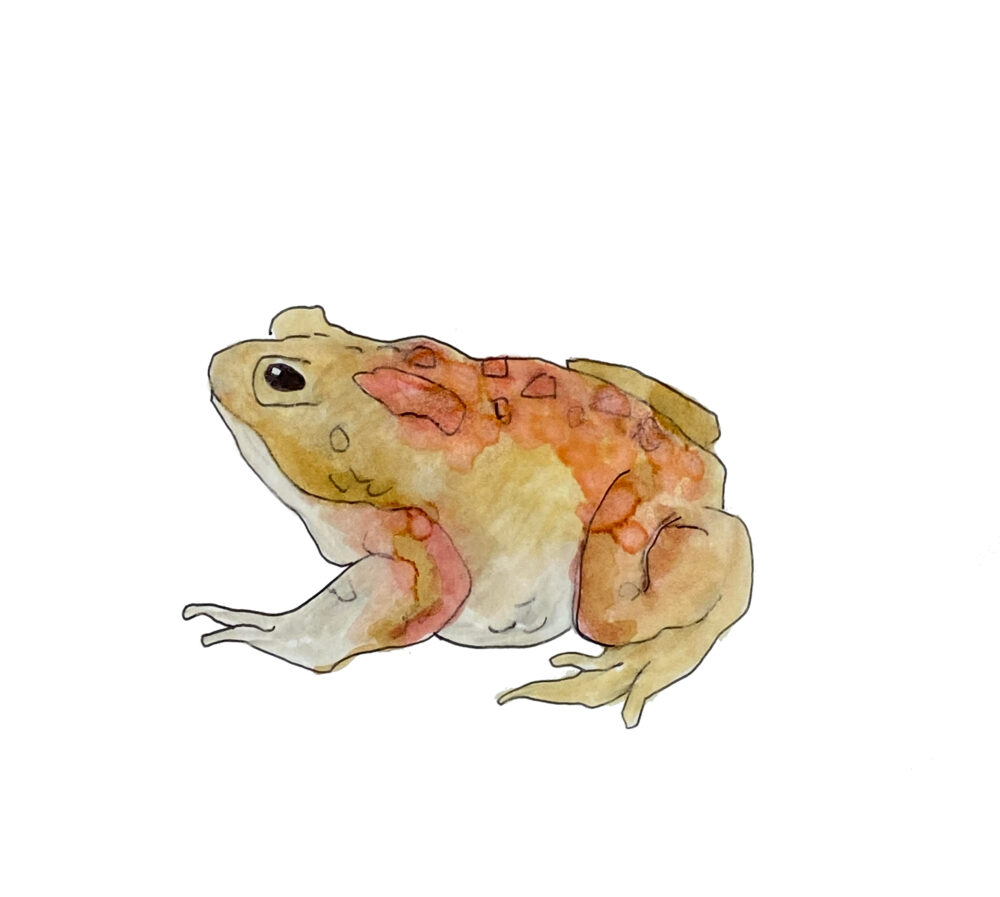

American Toad

Anaxyrus americanus

The males puff out their large throat, like an inflated balloon, to produce one of the most notable mating calls: a long 4-20 second trill. When threatened, they will crouch and remain still, relying on camouflage to protect themselves.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

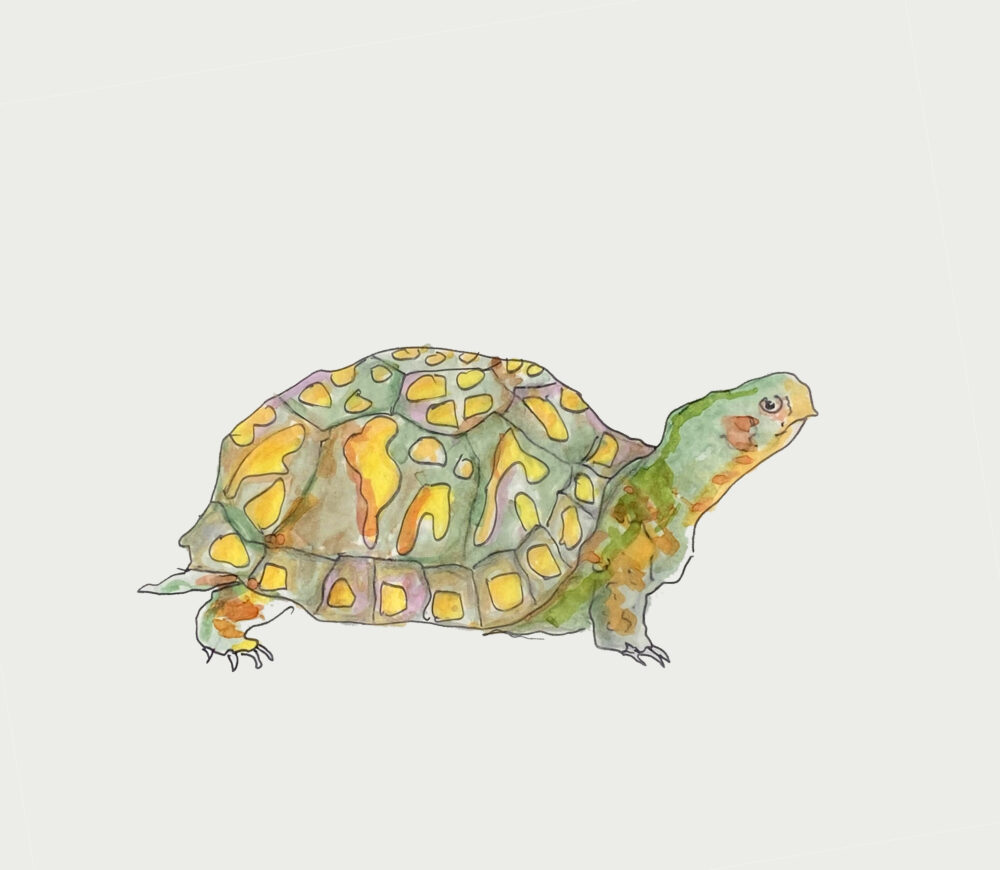

Eastern Box Turtle

Terrapene carolina carolina

These turtles are old souls; they generally live for 25-35 years, but have been known to survive to over 100 years old. They love to bask in the sun, but in the winter they enter a hibernation-like state known as brumation.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

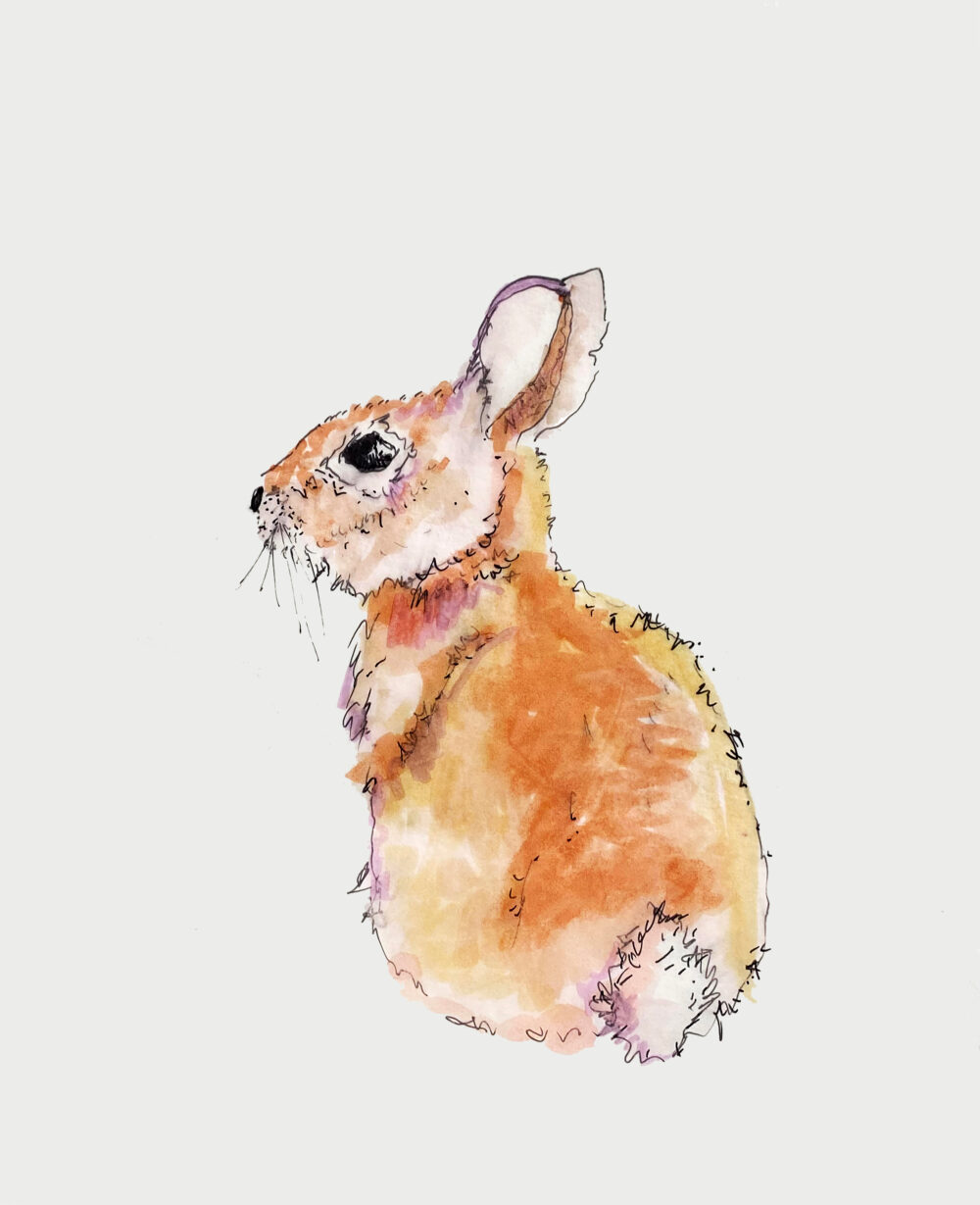

Eastern Cottontail

Sylvilagus floridanus

While being pursued by predators they can reach speeds up to 18 miles per hour and often zig-zag to confuse them. Baby rabbits are called kits, adult females are does, and males are bucks.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

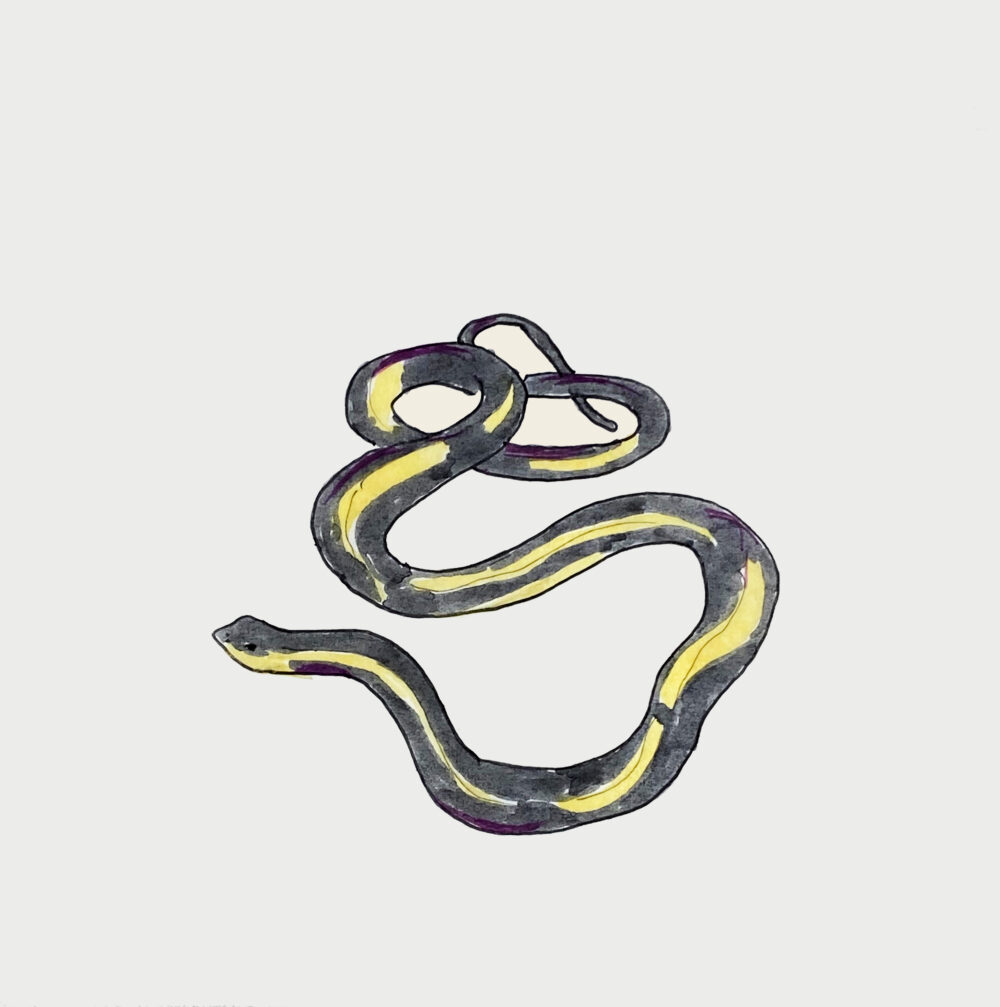

Garter Snake

Thamnophis sirtalis

They are among the most common snakes in North America, with stripes running lengthwise. The offspring are hatched from eggs within the body of the parent – 20 to 40 at one birth. Once they are born, the baby snakes live on their own.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Great Horned Owl

Bubo virginianus

The largest of the “tufted” owls, the bird’s acute hearing allows it to hear sounds from 10 miles away. The shape of their wings and softly fringed feathers allows them to fly in near silence.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Largemouth Bass

Micropterus Salmoides

Largemouth bass are the most popular freshwater game fish on Long Island. Largemouth bass can see well in all directions except straight back and straight down. Their excellent vision helps them see most of the same colors as humans. Bass uses their lateral lines to “hear” or detect sounds and vibrations from up to 100 feet away.

Osprey

Pandion haliaetus

To court their partner, males perform a ‘sky dance’ where they hover and wobble in flight while screaming to attract a female. These birds lay their eggs asynchronously with three being the usual number. Their arrival to eastern Long Island, typically in mid-to-late March, coincides with the arrival of spring.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Raccoon

Procyon lotor

Raccoons are nocturnal animals – which means they sleep during the day. The black mask around their eyes works to absorb incoming light and reduce glare, helping them to see at night when they are most active.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Red-Winger Blackbird

Agelaius Phoeniceus

They are considered a harbinger of spring as they return to wetland areas around early March. The larger the red band of its shoulder (epaulet) the more attractive it is to females. They nest in the marsh grasses.

River Otter

Lontra Canadensis

River otters are recovering on Long Island from their near extirpation. They spend most of their time on land, but their main sources of food are aquatic prey. On land, they can travel between waterbodies and watersheds at speeds of up to 18 mph.

Spotted Salamander

Ambystoma maculatum

These blueish-black salamanders are large, about 6-10 inches. Since they lay their eggs underwater, the larvae are born with external gills for breathing in their aquatic habitat. Their striking coloring alerts predators to stay away, but just in case they secrete a milky toxin from their backs and tails.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Whitetail Deer

Odocoileus virginianus

They are primarily crepuscular, meaning they are most active at dawn and at dusk. These abundant creatures have a very diverse plant-based diet, including nuts, fruits and berries, grasses, fungi/mushrooms, twigs, and even poison ivy.

Artwork courtesy of Amy Foster, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Wild Turkey

Meleagris gallopavo

An adult turkey has 5,000 to 6,000 feathers. Their droppings tell a bird’s sex and age: male droppings are j-shaped while the female’s droppings are spiral-shaped; and the larger the diameter, the older the bird.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Wood Duck

Aix Sponsa

Due to over-hunting as well as destruction of habitat, wood duck numbers were very low in the late 1800s and early 1900s. With conservation efforts, there are now over a million wood ducks in North America.

Insects

Dragonfly

Anisoptera

Dragonflies are expert fliers. They can fly straight up and down, hover like a helicopter, and even mate mid-air. If they can’t fly, they’ll starve because they only eat prey they catch while flying.

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

These pollinators have four generations each year, with the butterflies emerging in September and October making a trek south to overwinter. The first three generations live between two and six weeks. The fourth generation travels to Mexico for the winter, flying up to 100 miles daily during a 3,000-mile migration.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Water Strider

Gerridae

The Gerridae are a family of insects in the order Hemiptera, commonly known as water striders, water skeeters, water scooters, water bugs, pond skaters, water skippers, or water skimmers. Their physical structure allows them to displace water and create surface tension, which allows them to run across the surface of water.

Plants

Highbush Blueberry

Vaccinium corymbosum

The blueberry is one of the only foods that is naturally blue in color. The pigment that gives the blueberry its distinctive color, anthocyanin, is the same compound that provides the blueberry’s amazing health benefits.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

New York Aster

Aster novi-belgii

A flowering plant that blooms in the late summer with purple flowers, the name “aster” originates from the Greek word for star, referring to the star shaped flower heads.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Red Cedar

Juniperus virginiana

The berries on these trees are not berries at all – they are cones, like pine cones. These “berries” are an important food source for many birds, especially in the winter months. The smell this tree makes is unpleasant to moths, and a reason why closets and storage trunks are lined with cedar.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

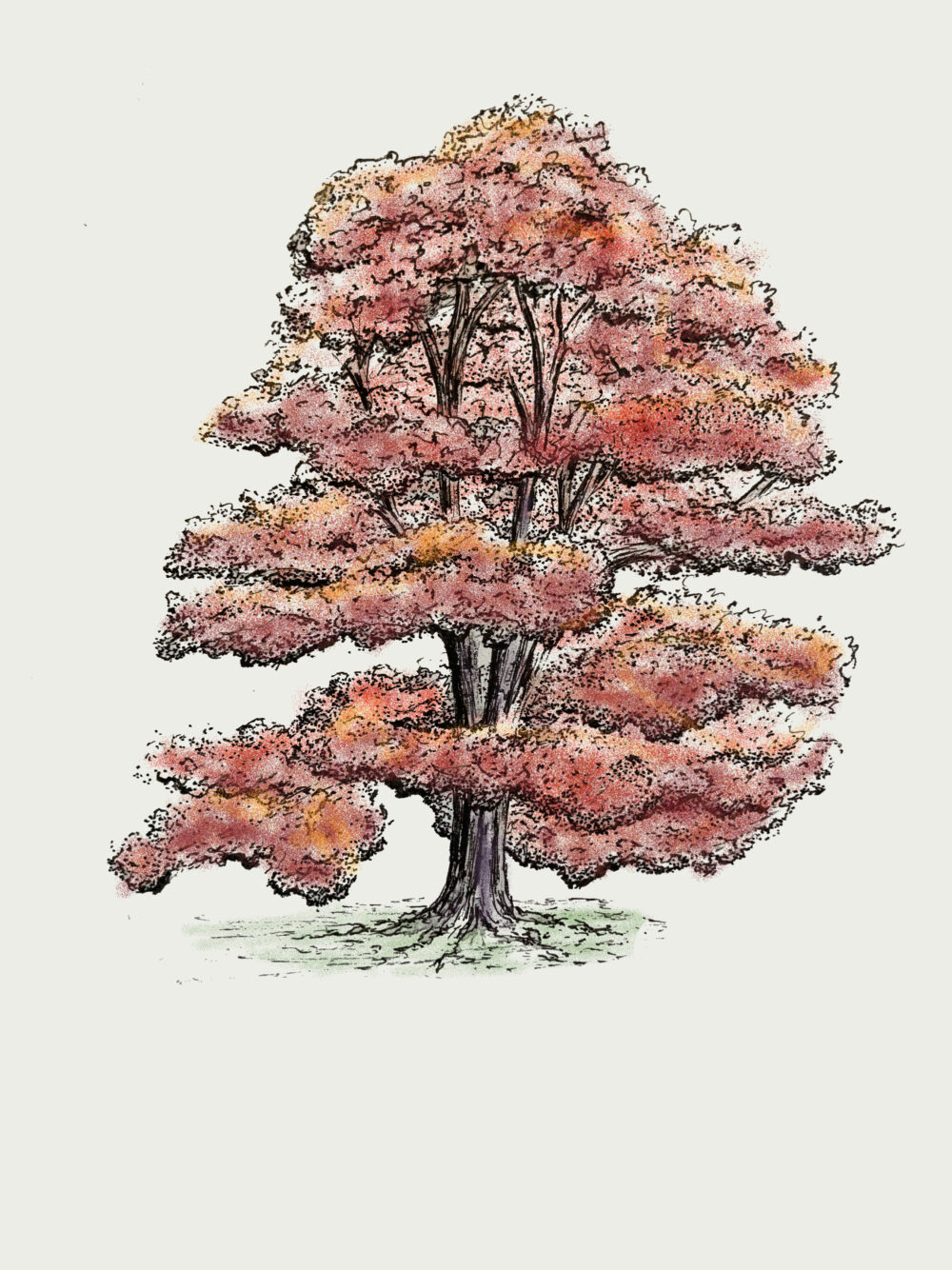

Red Oak

Quercus rubra

Instead of being smooth, the leaves of these trees are usually a bit furry on the bottom – and its leaf stalk is often slightly red, one of the reasons for its name. The acorns from the tree are used as a food source by blue jays, squirrels, raccoons, and wild turkeys.

Artwork courtesy of Mark Tepper, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Sassafras

Sassafras albidum

This tree has polymorphic leaves, which means there are different types or shapes of leaves on the same tree: oval, mitten-shaped and three-lobed. The tree is also known to repel mosquitoes and other insects.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Seaside Goldenrod

Solidago sempervirens

The plant is commonly found on beaches and dunes. Its waxy, fleshy leaves help the plant retain water and it is tolerant of saltwater spray and rock salt. Flowering in late summer, it is an important habitat and food source for shoreline birds and monarch butterflies.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Silver Birch

Betula pendula

This tree produces fruit called a “samara,” and can release around one million seeds each year. Both the seeds and the bark of the tree are food sources for forest animals, including deer, rabbits and birds.

Artwork courtesy of Britt Zuckerman, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

Switchgrass

Panicum virgatum

This native North American prairie grass offers excellent forage and habitat for birds and butterflies. When it first blooms, it produces pinkish seedheads, with the grass turning to yellow in the fall.

Artwork courtesy of Amy Foster, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

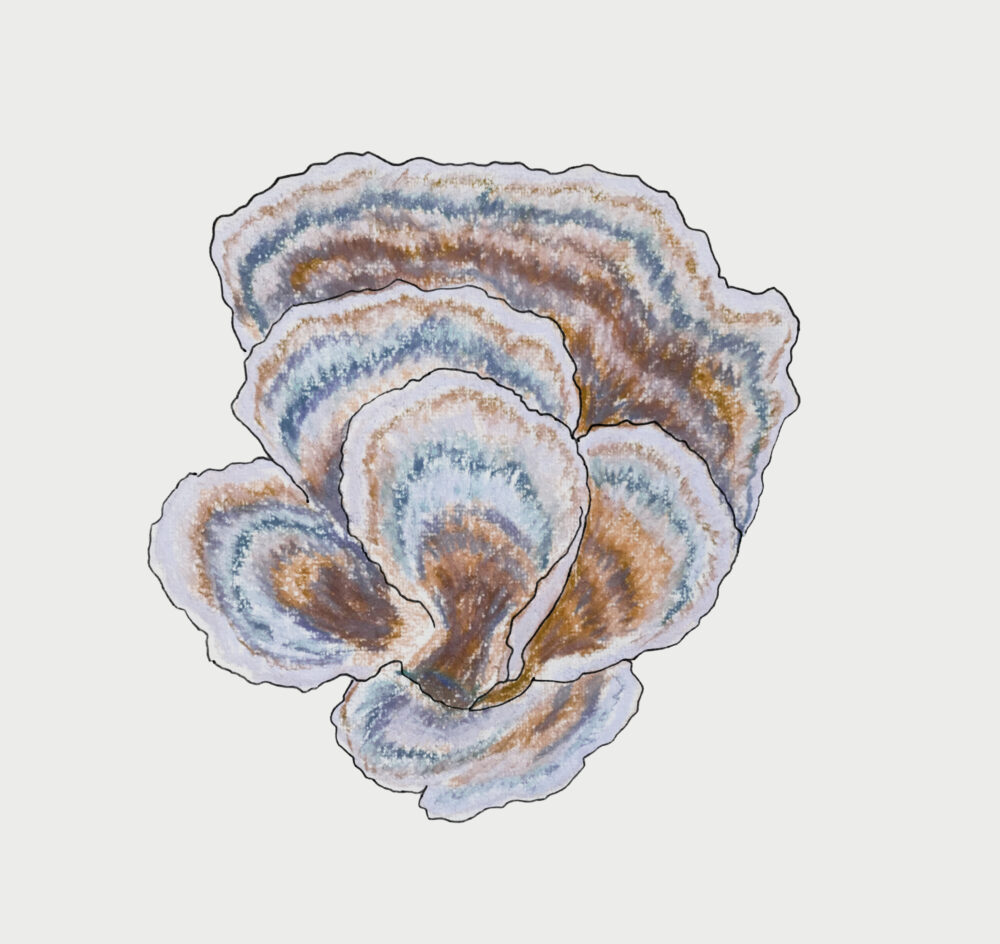

Turkey Tail Mushroom

Trametes versicolor

It’s easy to see why this fungus is called the “Turkey Tail,” as the upper surface sports rings of color that vary from grey to brown to reddish-orange. This fungus breaks down the dead wood on a tree for nutrients while helping clear the area for new growth.

Artwork courtesy of Amy Foster, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

White Oak

Quercus alba

These trees can live for centuries and typically don’t start producing acorns until they are between 50 to 100 years old. Once mature, they can produce more than 2,000 acorns a year, but only 1 in 10,000 become an oak tree. Another unique feature: these trees produce both male and female flowers.

Artwork courtesy of Amy Foster, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C

White Pine

Pinus strobus

Found in the eastern part of the United States, the trees can grow for 200 years or more and up to 150’ tall. The tree’s needles typically grow in bundles of five, which distinguish it from the other pine found on Long Island— the Pitch Pine— which typically grows in bundles of three.

Artwork courtesy of Amy Foster, of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture P.C